Agnes Beddoe, the wife of Dr. John Beddoe, founded the Bristol Emigration Society in 1882. Although a Society in name, it was, in reality, no more than a loosely bound group of individuals, each claiming responsibility for only a small segment of the children emigrated. This situation became a source of frustration for Canadian immigration authorities.

Having worked with the noted reformer, Mary Carpenter, at the Feeding Industrial School and Mary Carpenter’s Home for Working Girls, Mrs. Beddoe established a similar home in Bristol. Influenced by Miss Carpenter, she was convinced that emigration was in the best interests of the children.

Mark Whitwill, a civic politician and local entrepreneur involved in the shipping industry, shared Mrs. Beddoe’s enthusiasm for child emigration particularly children housed in the industrial schools. In 1883, he lobbied for the inclusion of Poor Law children in the emigration program. To defuse opposition to his proposal, he personally funded the cost of passage for wards of workhouses.

Whitwill gained a strong ally in Mary Clifford, a member of the board of guardians of the Barton Regis Union. Miss Clifford was a devout Christian, concerned with the plight of women, children and the elderly being kept in workhouses. Typical of many zealots, Miss. Clifford practiced “The ends justify the means” approach to the process. She believed that the children’s salvation could only be achieved by insulating them from previous influences; sending them to Canada was an ideal solution. Miss Clifford was ruthless in the application of her doctrine, going to whatever lengths necessary to deny parents any knowledge as to the whereabouts of their children.

The Society sent its first group of children to Canada in 1886. Having no receiving home of its own, the Society placed children through an immigration agent in St. John, New Brunswick. Some were sent to Marchmont in Belleville, teenage girls to Montreal and a few were dispatched to Winnipeg. Those placements aside, the majority of the children would remain in New Brunswick.

The Society’s lack of structure or indeed any semblance of organization led to numerous unsatisfactory situations. Without a receiving home to accommodate the new arrivals, children were immediately sent to farms and put to work.

The Society required no formal agreement between itself and host farmers nor was there any record of where the children had been placed. Without a written contract spelling out the obligation of the farmers, great reliance was placed on verbal agreements to house, clothe and feed the children. Noticeably absent from the arrangement was any undertaking to educate or pay the children. Farmers routinely loaned the children to other farmers without maintaining any record of their change in situation. Follow-up inspections by the Society were rare, if any.

In some cases, the children were sent unescorted and with no provisions made for their upkeep upon arrival. Understandably, several children believed they were masters of their own destiny and simply wandered off to make their way in the world.

Canadian immigration authorities became increasingly concerned about the Society’s haphazard operations and the plight of the children they brought to Canada. Attempts to determine the children’s welfare were confounded by the fact that many of them were simply missing and unaccountable for.

The government’s attempts to bring change to the Society’s practices were hampered by the fact that there was no singular head of the organization and little collaboration between the individuals sending children abroad. Whitwill would only accept responsibility for the children sent from industrial schools. Mary Clifford and her assistant Margaret Forster would limit their responsibility to those sent from workhouses. In each case, both groups would abdicate any responsibility for children sent by the other.

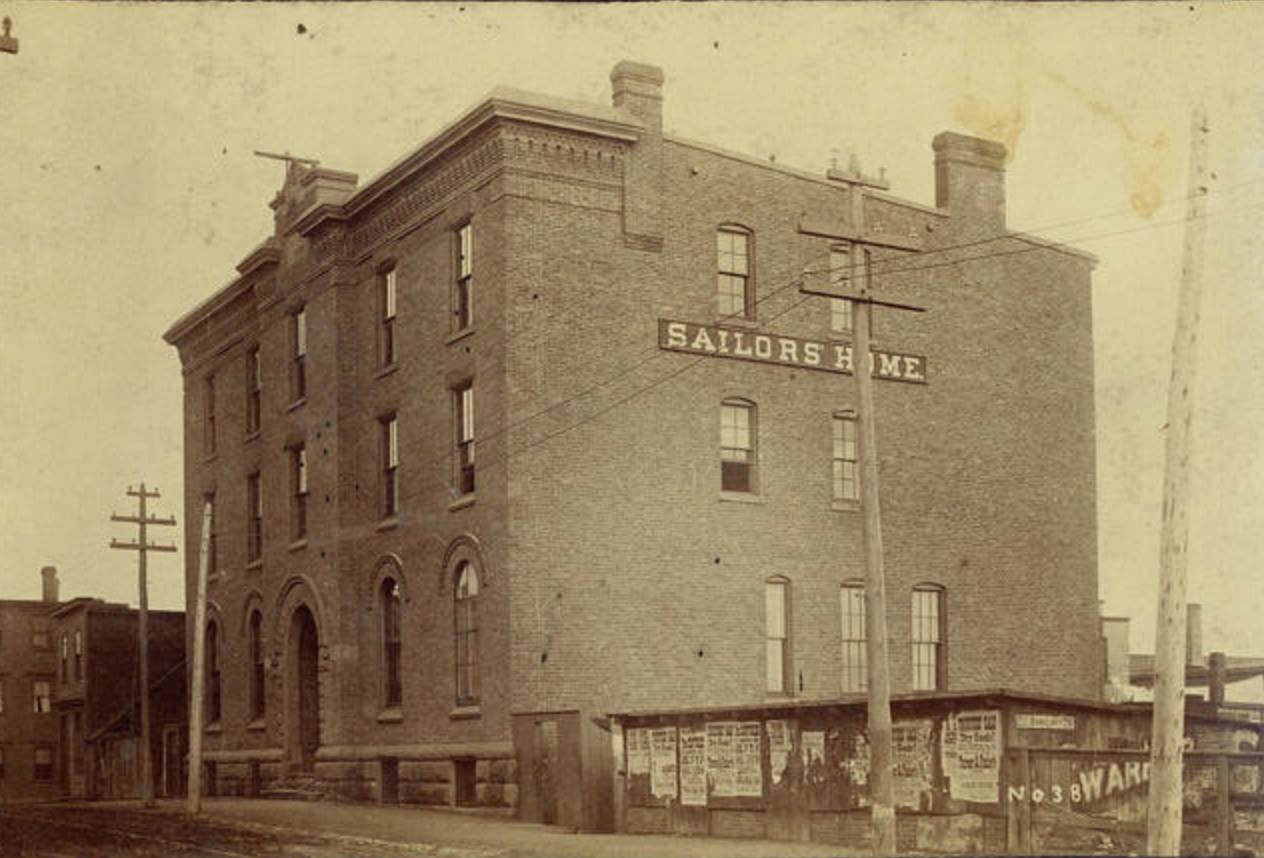

At the urgings of the government inspector, Mr. Smart, the Society began entering into written contracts with New Brunswick farmers. In 1903, Smart further reported that the Society was using the Sailors’ Home in St. John as a temporary receiving home until a permanent home could be established.

Coinciding with Whitwill’s death in 1903, a committee headed by the Lord Bishop of Bristol was struck to oversee the formalization of the Society’s operations. Before anything meaningful was accomplished, the Society ceased operations.

In 1906 the Bristol Emigration Society sent its final party of children to Canada. This last group of seventy-two brought the total number of children sent by the Society to three hundred and twenty. The Society ceased operations in much the same way it had conducted itself from the outset; abandoning any further responsibility for the welfare of the children it had sent overseas.